Originally posted on my substack, December of 2025.

I recently heard someone say ‘everyone just seems to be sleeping on geothermal.’ I certainly have been, and this has been the case in many of the social and intellectual spaces I spend time in.

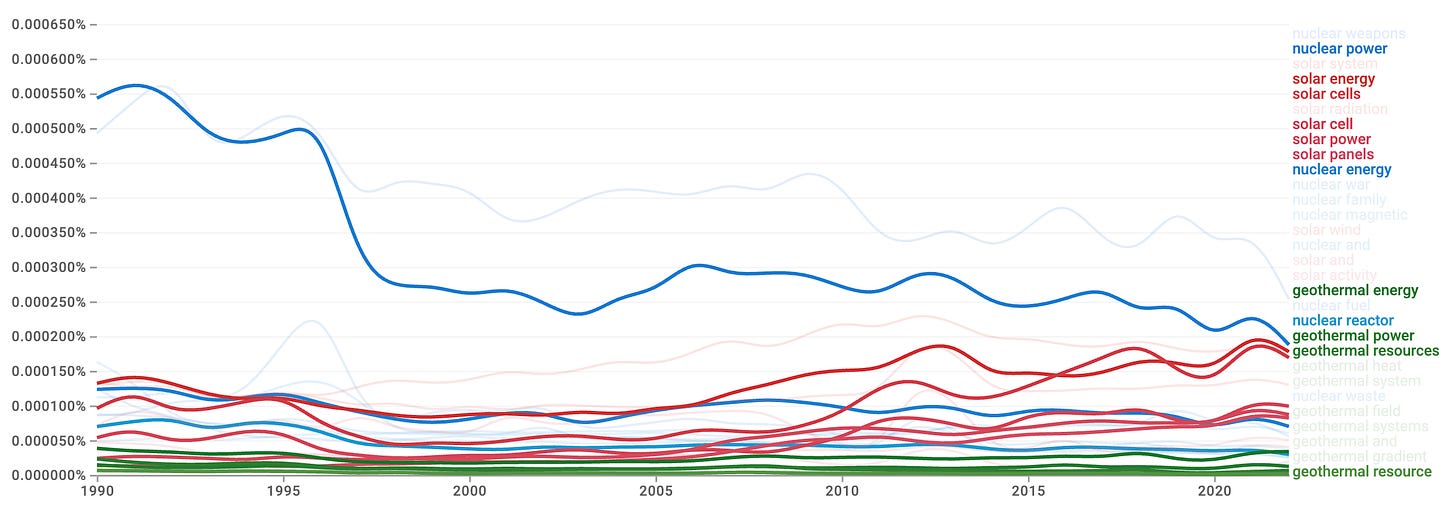

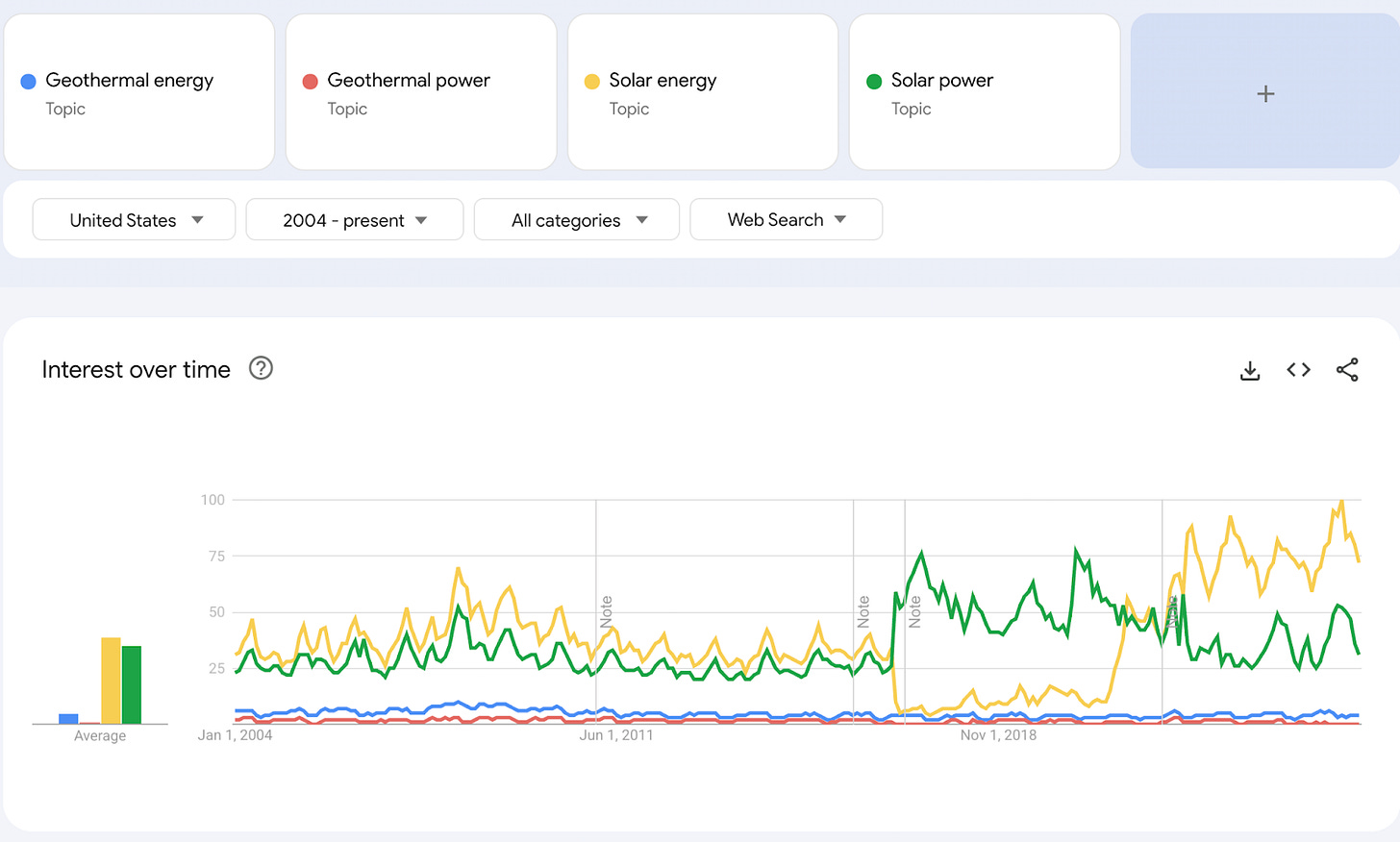

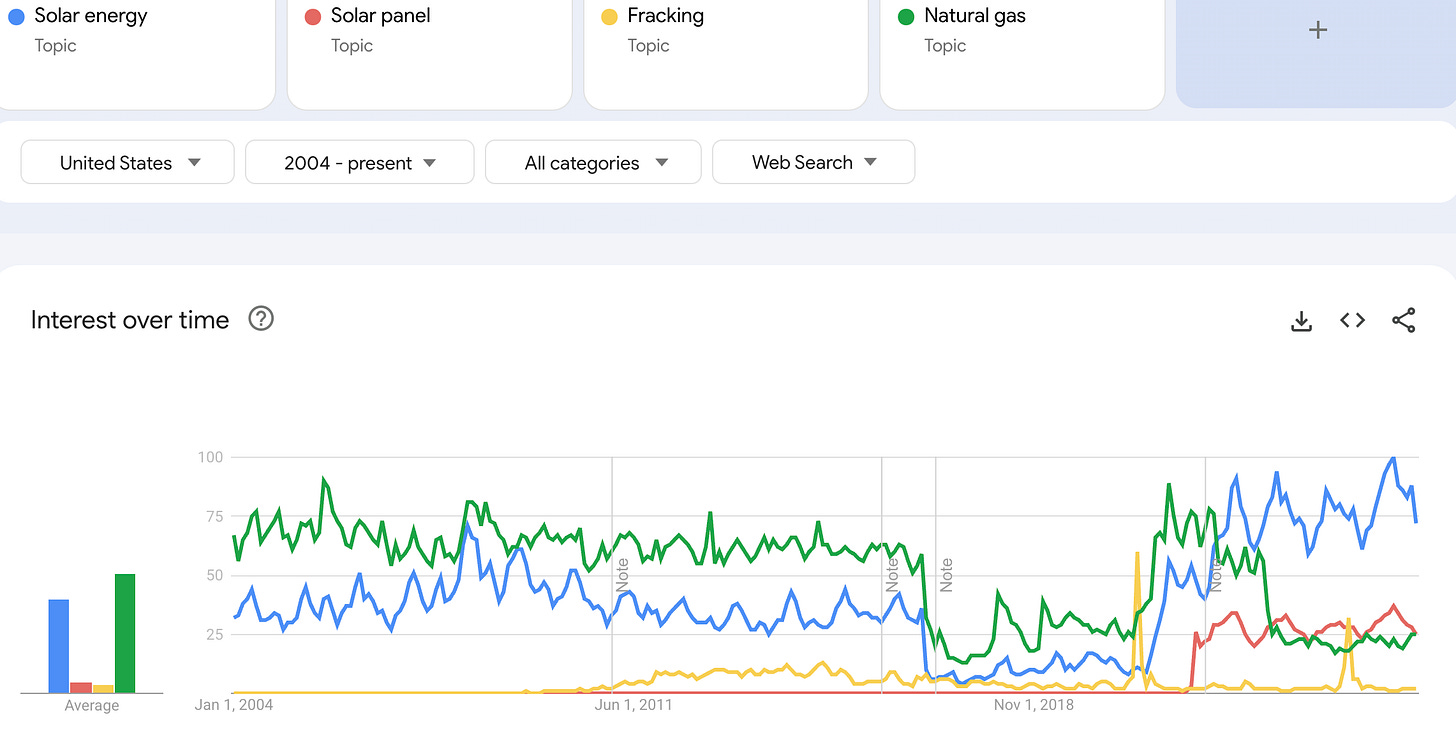

I imagine there are plenty of circles where it comes up frequently. There are some great writeups (Eli Dourado, IFP, Prime Movers), and there’s some exciting popular coverage / press (e.g. recently The Economist, or Bloomberg on Mazama). Geothermal was also only like .4% of US generation in 2023, so one wouldn’t expect it to come up as often as more prominent energy generation methods (with more current deployment, and with histories of both demonization and evangelism). Still, solar was less than .1% of the US grid in 2010 and hit 1% in 2015 - but entertained far more interest long before, during, and since then (see the graphs below).

Regardless, I wanted to learn more, so I read up and attended a demonstration of Quaise’s drilling technology an hour out of town (Austin), in Marble Falls, TX. Both of these compounded my sense of opportunity: the scale of the resource availability is striking, and there’s remarkable work being done towards making it more broadly economical.

Work by the Clean Air Task Force’s (CATF’s) found that “harnessing just 1% of global SHR [super hot rock] potential could generate 63 terawatts (TW) of clean firm power,” while the IEA estimates that:

The amount of electricity that could be technically generated by EGSs for less than USD 300 per megawatt-hour (MWh) using thermal resources within 8 km of depth is about 300 000 exajoule (EJ). This is equivalent to almost 600 terawatt (TW) of geothermal capacity operating for 20 years – exceeding the technical potential of conventional geothermal by almost 2 000 times.

The magnitude and availability of hot rock resources seem to have been well understood for some time–this is from an MIT report written in ‘05-’06:

Most of the key technical requirements to make EGS work economically over a wide area of the country are in effect, with remaining goals easily within reach. This achievement could provide performance verification at a commercial scale within a 10- to 15-year period nationwide.

...

Using reasonable assumptions regarding how heat would be mined from stimulated EGS reservoirs, we also estimated the extractable portion to exceed 200,000 EJ or about 2,000 times the annual consumption of primary energy in the United States in 2005. With technology improvements, the economically extractable amount of useful energy could increase by a factor of 10 or more, thus making EGS sustainable for centuries.

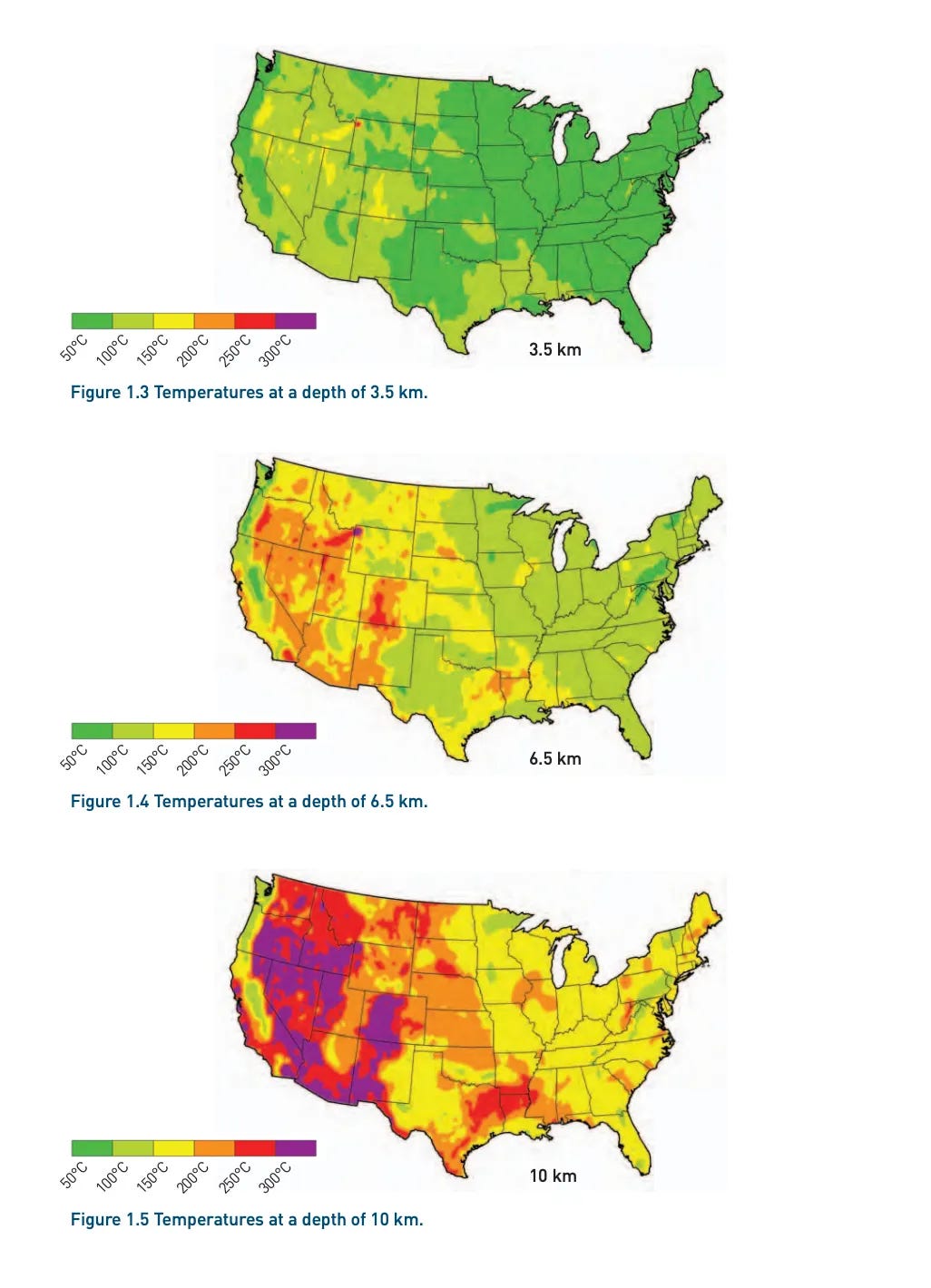

It’s been 20 years since that writing, and I don’t think we have nationwide commercial verification - perhaps the report was slightly technically optimistic, or perhaps not enough capital (human and otherwise) went into the field. I assume the shale revolution also made it much less economically appealing. I’d love to find a retrospective. Regardless, there is currently a good deal of exciting industry activity, focused in the west (e.g. see map of projects at different stages; Prime Movers Lab superhot rock landscape list in here).

Within all the ongoing work, cheaper drilling through hard crystalline rock like granite to reach deeper hotter rocks, seems the highest upside area of work. Access to higher temperatures unlocks both generation efficiency and geographical availability. I find these heat-depth maps useful for visualizing how depth unlocks heat in different geographies.

Generation efficiency improves as temperatures increase, but there’s a step increase when water goes supercritical (at 374C and 22 MPa). A supercritical fluid lacks differentiable liquid and gas phases, and can transport thermal energy notably more efficiently than steam. This makes reaching the requisite ‘super hot’ rock of >400C (about the same temp as a professional brick pizza oven) a particularly promising objective. This Clean Air Task Force quote lines up the efficiency benefits of systems at 400C:

Higher temperatures also significantly increase thermal efficiency, as shown by the Carnot cycle. As an example, geothermal systems operating at 150-180 °C achieve about 12% electricity conversion efficiency, while concentrated solar power (CSP) systems at 400 °C reach nearly 40% and CSP systems at 1,300 °C can achieve close to 60%. This increase in thermal efficiency translates to more economical operations by maximizing enthalpy per unit mass and generating more energy from the same mass flow rate.

However, reliably reaching high heat or super-hot rock is expensive — equipment fails against hard rock and has to be replaced at great cost. Quaise’s approach to this problem is to use millimeter waves to melt the rock (without ever touching it). As mentioned, I recently attended a demonstration of this process.

Quaise

Millimeter waves sit between microwaves and infrared light on the electromagnetic spectrum. The gyrotrons that produce the waves are typically used in fusion reactors to heat plasma. In Quaise’s case, they’re beamed down a well to melt rock. This youtube video with Henry Phan, the VP of Engineering, explains the technology well.

The result is strangely beautiful and clean. The surface of melted granite samples is glassy and smooth and the byproduct is a fine gray ash that gets pushed or lifted out of the well by a ‘purge gas’ (compressed air or nitrogen) emitted from the drill tip.

The team demonstrated the process by drilling a 100m hole at a granite quarry in Marble Falls. I attended as someone interested in the technology and its potential benefits, with no stake other than curiosity, a desire to cultivate my own industrial literacy, and strongly wanting to see much more cheap energy production in my lifetime.

To clarify, what it was not: it was not like a ‘demo day,’ nor was it a quirky demonstration of a lab result, nor a startup pitch developed after a few months of incubation, nor a corporate ‘dog and pony show’. It wasn’t theatrical and it wasn’t a nerd party.

It was: a technical demonstration used to educate relevant stakeholders and potential investors on the actuality of drilling with a beam of photons. The technology has spent plenty of time in the lab - years at MIT before Quaise was founded in 2018. This was a demonstration of current field capabilities relevant to fulfilling a 3-5 year plan, including several commercial projects. I found the event tone clear, frank, and energized. Every engineer that I spoke with or heard present was excited about the technology - they are, after all, melting rocks with microwaves - but there was a clear drive towards benchmarks and a lot of thought put into optimizing the system for deployment and operation.

We were able to see the rig in operation, the resulting smooth interior of a prior bore, the gyrotron set up in a shipping container, the cuttings (ash) outtake system, and the monitoring systems. I had partly hoped the demonstration would be dramatic (something like Edison’s illumination of the NYT building in The Gilded Age), but the working demonstration consisted of watching several different live measures progress on graphs in real time (RF power, vertical position, tension, and distance to well bottom), which seemed appropriately dry and informative.

The team - or those I met - seemed ambitious and committed. There was neither bluster nor mincing words when Carlos described the goal of opening a resource space for the O&G industry to develop into - making it clear that the objective was for geothermal to be larger than oil and gas. He made that point once, then did not subsequently belabor it, which I appreciated.

Concretely, the setup was well-appointed for the context - there was a tent with bottled water and hard hats (QUAISE logos), and a security check-in at entry. Everyone on the team knew what they were doing. I half expected some anonymous wildcatter billionaire to show up in a worn F150 and start asking questions about ‘this whole geothermal thing.’ Maybe he was there. I’m not sure. I hope so. I equally expected to find a technology analyst from New York taking notes, a little weirded out and concerned because he has been writing about solar and nuclear for years, while geothermal was kind of just ‘the thing in Iceland powering some data centers’. He may also have been there in disguise, I’m not sure. (If you are either of those characters, I endorse you going to learn more). Judging by appearances, there were a mix of investors there, a couple interested lay-folk like myself, and at least one representative of a utility company.

There was also, appreciably, no science fiction bravado - and there easily could have been. The VP of Engineering, Henry Phan spoke and took us through the setup. He did mention The Core (2003) briefly by way of assuaging anyone who thought the technology sounded too much like fiction (Quaise isn’t using lasers to tunnel into the earth’s core and save the world, though there is, conceptually, an amusing bit of overlap).

They could have rattled off the eye-popping statistics up above or humble bragged about using fusion tech at a drill site. They could have repeated that geothermal is a baseload technology that already works really well when you have access to hot rock, while fusion is always 20 years away.

They could have emphasized the underestimation of the opportunity and flattered interested investors for seeing geothermal as an opportunity while popular tech-forward narratives have been kind-of sleeping on it and enthused about solar or nuclear for years.

Most important to me, there was none of the ideological baggage or fervor that I see around other energy technologies. It wasn’t narratively positioned/motivated as a way of running from the use of hydrocarbons, though clearly a benefit. The fact that their cuttings sequester carbon when encountering it was simply mentioned as ‘a ‘really nice side effect’ when someone asked a related question.

They didn’t complain about regulations holding them back (it was a bit more like ‘sure, permitting can be difficult - but this is the case in many industries; and they seemed to have plenty of contracts and prospects). I appreciated that the locus of control was nearer home. They didn’t talk about policy favorability from either party (geothermal sort-of has the blessing of the current administration) - no mention of relying on some particular regulatory outcome.

There totally could have been all of these things. Geothermal is clean, yet builds from expertise developed in the fracking boom (drilling, PDC bits, directional drilling, resource mapping). It’s the perfect opportunity for every left-of-center abundance enthusiast who’s always secretly wanted to yell ‘drill baby drill’ with a fake Texan intonation, but could only share solar-punk memes — and for every conservative who was loves O&G but is actually moderately bummed that sending hydrocarbon energy byproduct into the air at scale effects our atmosphere in a less than ideal way, and sometimes thinks EVs seem kind-of fun and zoomy. It even has potential for some sort-of naturalistic appeal – it’s really just a way of re-rooting civilization into the inherent warmth of mother earth if you think about it like a techno-optimistic hippie.

Drilling for geothermal also seems characteristically American, because we like to drill and because domestic resources (i.e. the relatively shallow hot rocks) are concentrated in the iconic terrain of the American West. At the same time, it is a globally available resource, provided you can drill deeply enough.

To be fair, the demonstration’s absence of ideological pomp is table stakes (or should be). Quaise is raising 200m dollars and nobody should invest that kind of capital because melting rock is cool or geothermal makes a nice story. It would be inappropriate to the context and stage of development. Besides, that’s not the point of a demonstration (they can give a Ted Talk if needs be) and their website hero lines provide ample narrative positioning: “Unlocking the true power of clean geothermal energy” and (nearer the bottom) “A truly equitable clean energy source, abundantly available near every population and industrial center on the planet.”

Still, the tone of the day and the people communicated something to me, as did the many examples of weighty granite turned to ash and glassy black residue (an oddly beautiful feature). I don’t yet have much sense of the economics (e.g. what’s the value of a deep well, how many wells do you need to drill to break even on a gyrotron, and how have gyrotron costs changed over time historically), but I’m optimistic about Quaise’s technical capabilities (based on the limited observational data I have). Their next steps included drilling a 1km hole with the current setup, followed by another 1km hole with a new setup (more powerful — 1MW, and larger diameter), which, if successful, then moves to deployment on a commercial project in the northwest.

From a technical perspective, the demonstration did clarify a lot of questions. Firstly, the cuttings. I was a bit skeptical / unclear on what sort of material was going to be removed via pushing a ‘purge gas’ through the well while drilling - seeing the fine-ness of the ash cuttings was helpful - it’s easy to imagine floating like snowflakes or soot off a fire.

I was also initially unclear on how the beam of photons / waves gets from a rather large gyrotron in a shipping container down into a well. The answer seems to be just like visible light - Quaise had built a set of linkages to direct the beam down the well. Interestingly, there’s negligible degradation of the beam as it travels (though changing directions does have a small cost).

Regarding the fracturing (which, of course, wasn’t part of the demonstration, but Henry spoke about), the process they’re pursuing is much slower and longer than in the case of shale fracturing for gas. The aim is to produce hairline fractures that maximize heat transfer (vs short circuiting the input-outtake loop with massive fissures). Using hairline fractures also reduces seismicity risks when compared with larger breaks. It remains an open question to me how one optimizes the fractures and how well understood fracturing granite is compared with shale. This seems like it was a challenge back in 2005, but I have to imagine that the shale revolution has improved fracture mapping immeasurably since.

One innovation that Brian Potter wrote about as essential to the shale revolution was improvement in directional drilling. This seems much less relevant for fracture based geothermal systems (drill two wells deeply then fracture to create flow between them), but Quaise is working on 45 degree directional drilling to have the optionality. I’m not sure of the use case, but it seems it would afford more precision.

In terms of power requirements, I heard during the demo that the gyrotron operates at about 45% efficiency, so to get 100kW down the hole, you need roughly 222kW and for 1MW you’d need 2.22MW. This lines up well with the power requirements of conventional drilling sites, which typically have 2-4MW of diesel generation onsite (or more for higher power drilling rigs). Improving gyrotron efficiency by working with suppliers seems to be a major focus (Henry noted that much greater efficiency has been demonstrated in lab contexts (something like 80%), so they know it’s doable.

In terms of power consumption, it’s easy to imagine MMW drilling as a ‘plug and play’ service, used only when conventional drilling hits the hard rock. The team also emphasized that the equipment was compatible with standard land rigs and, aside from the ‘bit’ (wave guide) and monitoring & operating interfaces (many screens of data), would be essentially familiar to the existing onsite team (who would need to keep adding linkages). Quaise can then operate as a drilling services provider specializing in unlocking the hottest and hardest rock.

I found this one of the most compelling aspects of Quaise’s approach - the inbuilt intention to ally with O&G. Much of the team came from O&G - Carlos, Henry, and the PM running the demonstration all came from Schlumberger. The intent to open up new opportunities for the industry to profitably deploy its expertise was clear. In terms of recruiting, it’s easy to imagine O&G engineers looking for novel problems to solve (or wanting to melt rocks).

Hiring PhDs familiar with gyrotrons seems more difficult (there can’t be many and they’re presumably focused on fusion applications). That said, I imagine there’s a large set of physics undergrads / masters / prospective PhDs who would love to work on gyrotrons for drilling, but don’t know it’s an option. I know they have the MIT research relationship from the founding research, though I also hope Quaise is working on an internship program and getting in front of students early.

Working with the supply chain and / or in-housing components in the coming years does seem paramount (they are working with suppliers on this) both because the possible efficiency improvements are substantial and because of long lead times and low volume. The Bottleneck Institute put together this useful resource on the gyrotron industry here. It also sounds like deep drilling equipment suppliers are in somewhat short supply.

Some topics that I didn’t think to ask at the time, but remain curious about include:

- Well completion (sounds like it can be challenging at depth)

- Gyrotron run-time constraints (see this podcast discussion)

- This prime movers writeup also notes that superhot rock can yield corrosive elements in water, which might pose challenges.

I’m really excited about Quaise’s work, and that of others in the industry. Part of me wishes geothermal would get the kind of attention and excitement that solar has for decades. On the other hand, it may be fine if it continues to fly slightly under the popular radar, garnering more specialized interest and making persistent improvements until it achieves quiet ubiquity.

In a reading discussion, a friend with a career in O&G commented to the effect of ‘if geothermal is going to happen, it’s going to be in the US, right now, because the expertise of the shale industry is so robust’. I hope it happens and, if this is advent of a new major energy generation industry, then I’m glad the team I met is part of the vanguard.

Thanks @Quaise for the day, and @James Gray for bringing me along, as well as for feedback on this writing. For more detail, my raw notes from the day may be viewed here. All opinions and any errors are my own.